“The challenge that faces the university is to foster an environment for critical dialogue while also maintaining a neutral relationship to the different cultural and religious values characteristic of our pluralistic society. The public should be encouraged to think of universities as a laboratory in which varying cultural and intellectual perspectives can interact. When art is permitted to function as part of this process, it can best serve the mission of the university and the community at large.” – Beauvais Lyons, 1991

Art is, in some ways, the litmus test for all discussions of intellectual freedom. No other discipline is fraught in quite the same way where matters of “freedom of expression” are concerned.

In 1955, prior to the University’s racial integration, Marian Greenwood completed her mural, “History of Tennessee,” for the recently opened Caroline P. Brown Memorial Center. The mural celebrated Tennessee’s diverse music history and natural resources. In 1970, the mural was vandalized, presumably because of the way it depicted African Americans. Phil Scher, Vice President for Operations, repaired and paneled over the painting, vowing that it would never be unveiled during his time at the administration. The mural was not uncovered until 2006, during a convention on racism and censorship. As of April 2016, it was on long-term loan to the Knoxville Museum of Art.

Marion Greenwood, “History of Tennessee,” 1955

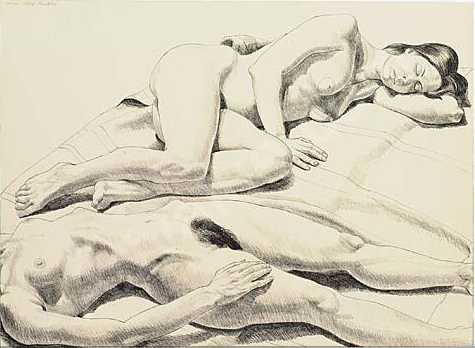

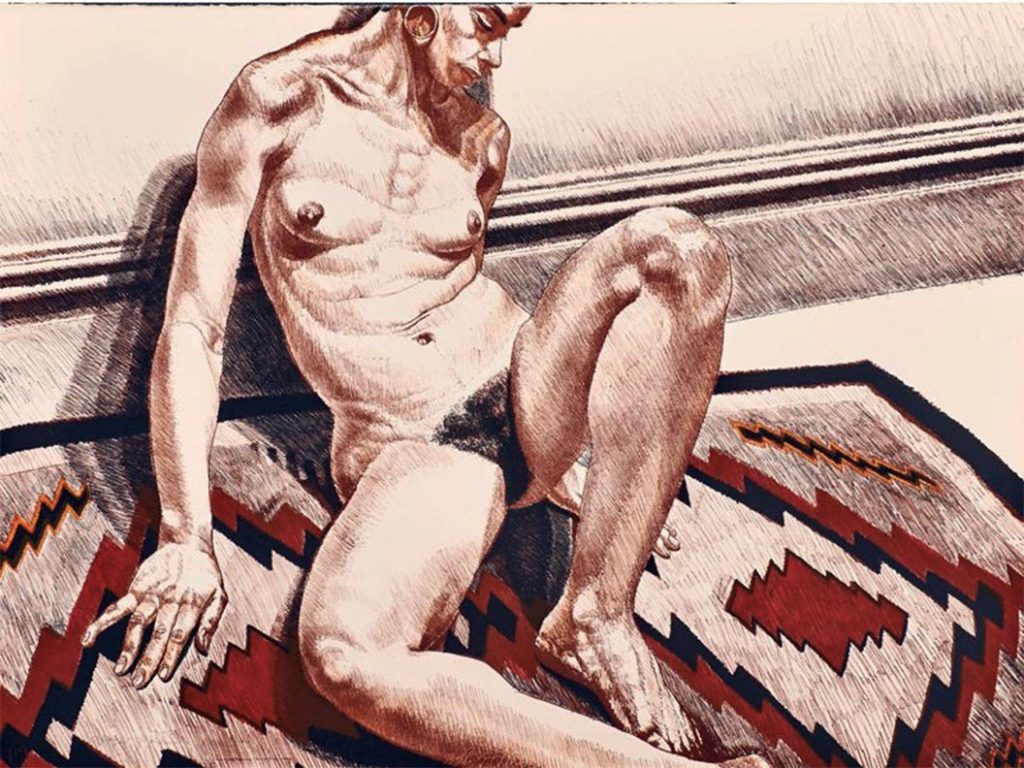

In 1981, the University brought some nude exhibits by the New York artist Philip Pearlstein to campus. They were originally displayed in the Concourse Gallery. This became controversial with the approach of Homecoming weekend. As Beauvais Lyons, current Chair for the Art Department, writes, “The chancellor feared that the images of nudes might offend members of the board of regents and several university benefactors who were scheduled to be on campus that weekend.” The chancellor therefore made the decision to relocate those exhibits to a less conspicuous space on campus.

In response, members of the faculty senate protested that the chancellor’s actions constituted censorship, and the local AAUP threatened to challenge the decision as a First Amendment violation. An independent faculty group also published a condemnation of the chancellor’s action as an abridgement of academic freedom. On the Monday following homecoming weekend the exhibition was rehung.”

The two images below are representative of Pearlstein’s distinctive style.

Philip Pearlstein, “Two Reclining Nudes”

Philip Pearlstein, “Girl on Orange and Black Mexican Rug”

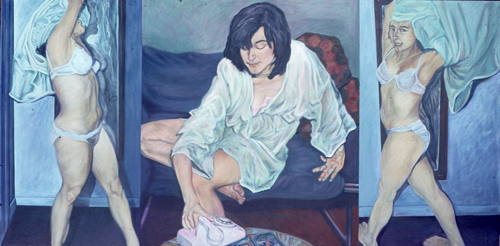

During the 1980’s, a graduate student (whose name is not included at her request) made a series of paintings depicting, according to her thesis statement, “the physical and lived relationship between mother and daughter.” The student prepared for the project by having her husband take a series of photographs of her and her daughter. When he took these images to a photo processing shop, that shop’s personnel misconstrued them as child pornography. Police subsequently confiscated the student’s paintings, over the protest of the Art Department head, Don Kurka. Police also confiscated art books depicting classical nudes in the student’s home, arguing that she was “an unfit mother.” The student agreed to take a leave of absence from the graduate program, and completed her thesis the following year. Faculty on her committee reported that she had added undergarments to her figures. “What is most troubling about this case,” notes Lyons, “is that the University made no effort to defend the artistic freedom of one of our graduate students.”

Special thanks to Beauvais Lyons for conducting research for this site.

___________________________________________________________________________

FURTHER READING

Beauvais Lyons, “Artistic Freedom and the University”

KNS Articles Discussing Pearlstein Controversy, November 19-December 2, 1982