“Democracy thrives on controversy, but it dies if you try to shut it up.”

– Dr. Henry Crane, Minister of Knoxville Methodist Central Church, 1958

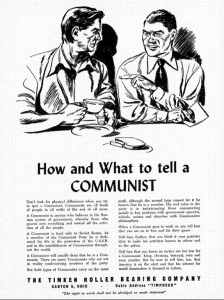

McCarthy-era pamphlet advising citizens to be vigilant in watching their neighbors

The story of the University of Tennessee during the Cold War is unremarkable in one sense: similar incidents were occurring at universities all across the country. Nevertheless, these vignettes still provide useful microcosms of the state of American intellectual life during these years, when paranoia and the fear of “subversives” often drowned out the voices of reason.

As early as 1947, the Truman administration was demanding “loyalty oaths” from government employees; and as early as 1948, a UT Professor could be accused of harboring “communist” sympathies simply for supporting Henry Wallace, the Progressive Presidential candidate. With the rise of McCarthyism in 1950, this paranoia escalated. Howard Lee Parsons, a professor in the Philosophy Department, had his first taste of the “Red Scare” in that year, when he asked a potentially provocative question on a logic exam. In the interview excerpt below, Dr. Ralph Norman, ’54, recounts his experience of taking that infamous exam:

Parsons found himself in the hot seat again a few years later, when he came afoul of the U.S. Senate’s International Security Subcommittee due to his affiliation with organizations committed to desegregation efforts in the South. Parsons was not fired for his efforts, but he was informed that he would not be eligible for any promotions or raises. Faculty members’ efforts to defend him proved to be in vain, and Parsons finally resigned in 1957.

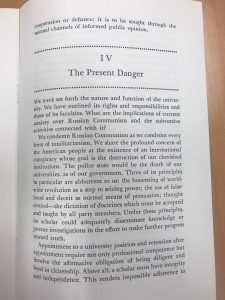

In its 1953 statement, the Association of American Universities reasserted their commitment to academic freedom for all professors — except for communists.

Red-baiters’ favorite targets, then as now, were textbooks. So it was that Fred Holly of the Economics department found himself under the scrutiny of a Tennessee Senate committee that had been charged with rooting out Communist influences in education. The committee took him to task for assigning textbooks that discussed such things as economic inequality and the possibility for socialized medicine. Holly managed to escape with his job after he assured the committee that he had only used the textbook for limited purposes. He later defended one of his department members, George Soule, from the charge of being a closet communist – a charge based on Soule’s affinity for Keynesian economics.

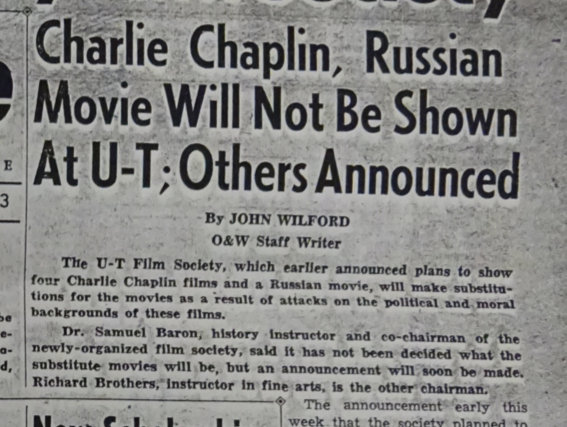

Local citizens proved to be more implacable than the Senate. Judd Acuff, a local assemblyman, attacked both Holly and the two History Department members, J. Wesley Hoffman and Sam Baron, as communists in disguise. Hoffman and Baron felt obliged to secure character testaments from, among other sources, local churches, war veterans, and students. Hoffman managed to maintain his job; Baron was not so lucky, and left the University in 1953 after being informed that his contract would not be renewed.

CIVIL RIGHTS ERA

Historians still debate the significance of the Cold War for Civil Rights. Some argue that it provided African Americans with an avenue for identifying themselves as patriotic participants in American democracy, while others insist that it led to Civil Rights activists being stigmatized and marginalized as “communists.” The case of UT in the 1950s and 60s certainly provides evidence for the latter interpretation. At the height of the height of the Red Scare, Howard Parsons was indirectly compelled to resign due to his affiliation with Civil Rights groups. This was merely a foreshadowing of things to come.

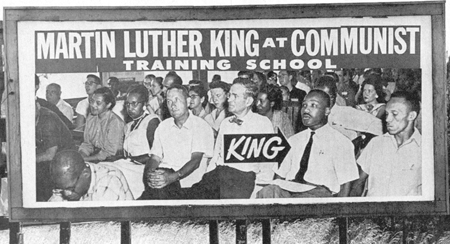

Martin Luther King, Jr. was accused of communist leanings for having spoken at the Highlander Folk School. This billboard was displayed in Knoxville during the early 1960s. UT professors who dared to associate with the Highlander School were subject to similar scrutiny.

By the beginning of the 1960s, the anti-communist paranoia of the McCarthy years had died down, but it certainly had not died. George Soule, an economics professor, came under the inquisitorial lens of local journalists for having dared to give a talk at the Knoxville Economics Club – a group headed by Lewis Sinclair, a black economist who also happened to be a director of the Highlander Research and Education Center. Soule subsequently found himself accused of Communist proclivities, allegedly due to his affinity for Keynesian economics. Fred Holly, the Department Head, and Andrew Holt, the University President, defended Soule as a perfectly patriotic professor. Holt even went a step further, reminding the accusatory Board of Trustees that even if Soule had been a communist, the University would still be perfectly within its rights to hire him. In response, the Trustees threatened to establish a committee to evaluate future faculty appointments. Holt stood his ground against such a proposition, and the Trustees grudgingly desisted. However, Holt did concede that no future faculty would be allowed to teach at the Highlander Center. In the ensuing five years, two faculty members, Ewell J. Reagin and Leroy P. Graf, would find themselves attacked as communists for attending Highlander Center events.

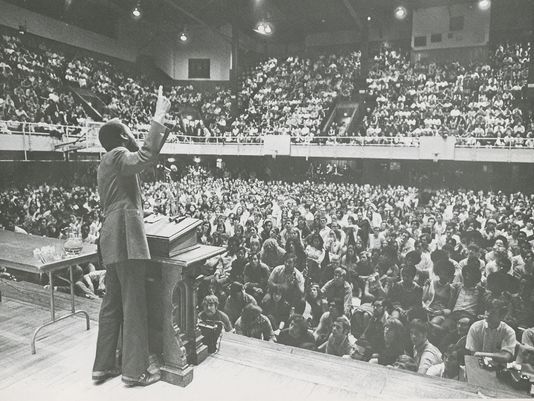

The Civil Rights Era also proved to be a watershed moment in securing the rights of student organizations. The galvanizing incident was the administration’s attempt to bar the comedian and social activist Dick Gregory (1932-2017) from speaking on campus. The ensuing debate has been discussed at length by Dr. Ernest Freeberg here.

Dick Gregory addressing students at UT in 1970

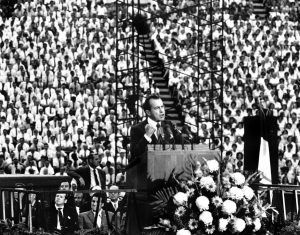

In May 1970, President Richard Nixon came to speak at Neyland Stadium as part of Billy Graham’s “Graham Crusade.” This was Nixon’s first speech at a college campus following the Kent State shootings, when political tensions over the Vietnam War were broiling.

Charles Reynolds (1939-2017), Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, led a group of students in protesting the President’s speech. The students held up signs saying, “Thou Shall Not Kill.” Law enforcement officials confiscated the signs and arrested 46 of the protestors, including Reynolds; all of the protestors were released with high bails.

Reynolds was ultimately fined $25. The Board of Trustees subsequently denied Reynolds’ application for tenure, but reversed their decision in 1974, by which time he had taken his case to the Supreme Court. It is unclear whether Reynolds ever paid the fine.

Students protesting Nixon’s appearance

Here Dr. Ralph Norman recounts his memories of Charles Reynolds during these years, and offers some of his thoughts on students protests:

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

LINKS FOR FURTHER READING

Academic Freedom during the Cold War

Miton Klein on Academic Freedom during the Cold War

J. Wesley Hoffman Papers on Academic Freedom (UTK Special Collections)

Speaker Ban Controveresy

“Inviting Controversy: When Tennessee students demanded free speech rights, half a century ago.”

SGA Report on Speaker Ban (1968)

Nixon-Graham Incident

“Billy Graham, Richard Nixon, protests came to Neyland in May 1970.”

Richard Nixon’s speech at Neyland Stadium.

Faculty Senate’s Report on Student Demonstrators.

Obituaries